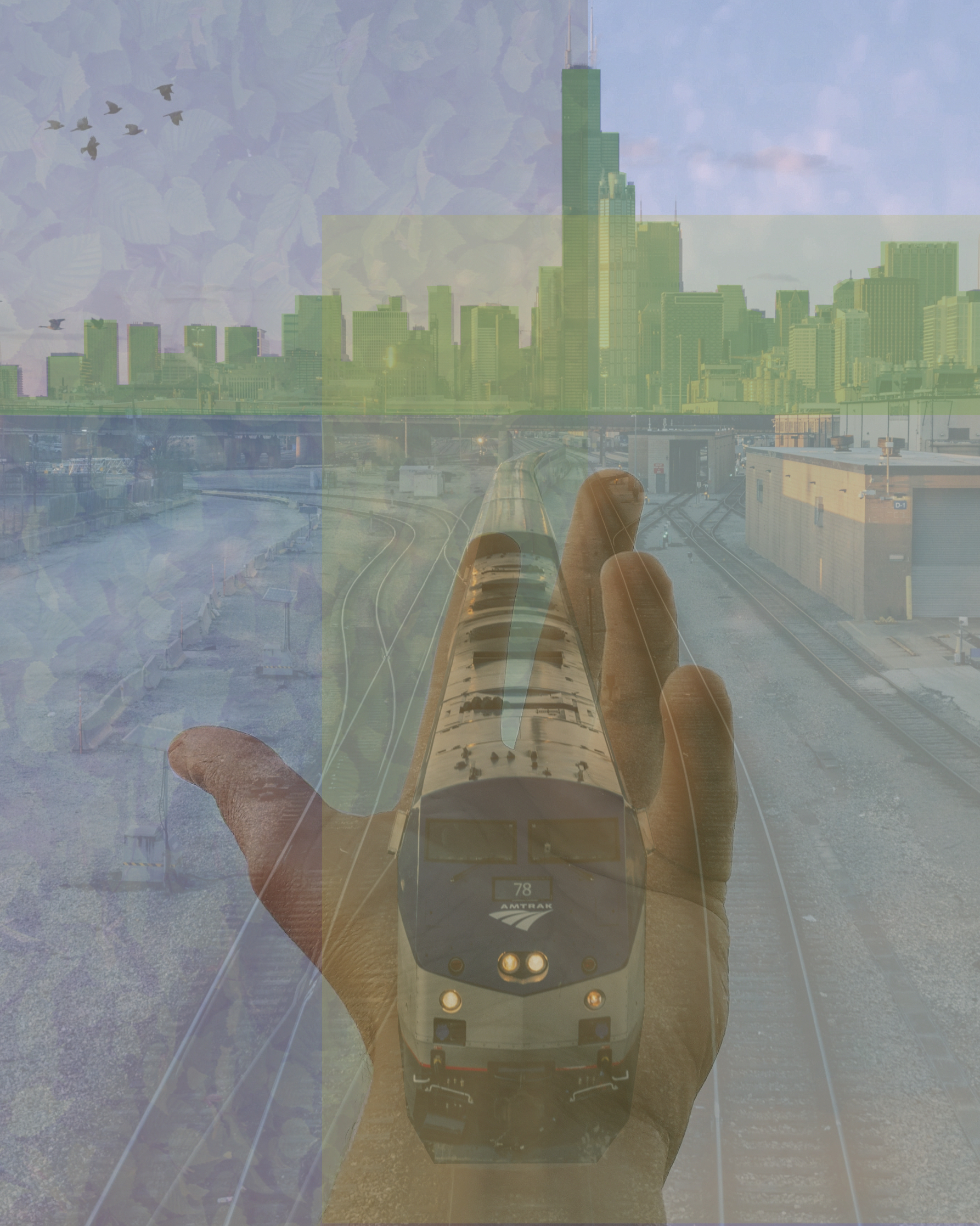

Will We Build Cities for Humans or Machines?

After decades of cities built for machines, will we return to cities built for humans? A changing climate and advancing technologies open doors to reimagine the future of transportation.

In October of 2023, I interviewed research ecologist Adam Terando along with drone aficionado Evan Arnold and public transportation systems researcher Kai Monast about the future of transportation. As climate change and advanced technology accelerate, we explored a unique opportunity to rethink how people, goods and ideas move around the world. We imagined futures where taxis fly down highways in the sky, driverless cars speed down autonomous-mandatory highways, emergency response drones deliver life-saving devices and high speed electric rail replaces fossil-fuel passenger planes. We traveled to a time when parking lots and personal cars are a thing of the past. We envisioned safe, reliable, affordable and environmentally-friendly transportation that is chosen, not imposed. We even asked ourselves, why move at all? While no future is certain, and ideal futures vary from person to person, our chat revealed one question we should all be asking about transportation of tomorrow: Will we build a future for humans, or machines?

This interview, conducted for the Long View Project, has been edited for clarity.

Transportation then and now: From feet to steamships to flying cars

Transportation involves moving people or goods from one place to another, does it mean anything different or special to you?

Kai Monast: I think it also includes moving ideas. The internet is an example of transportation. And Zoom. Before remote meetings, when people got to a place for a meeting, they would essentially move ideas. Now we’ve just skipped the whole personal movement part, and we’re moving the ideas directly.

Adam Terando: It’s part of that “annihilation of space by time” sort of thing from Marx. He talked about that around 150 years ago, how transportation shrinks physical space through technology.

Can you expand on that for those who aren’t familiar?

Terando: It was just an observation that Marx made about how capitalism has fundamentally transformed human societies after thousands of years. Somewhat similar, at least since the advent of agriculture, was, in that time, things like steamships, railroads and the telegraph, which is like the forerunner of the internet. Those were all ways to basically shrink time, as the phrase goes: “the annihilation of space by time.” You’re no longer bound to human or animal locomotion in order to transport people, goods or ideas. Fundamentally, that was one of those accelerant processes that modern day capitalism and the Industrial Revolution brought about. It had fundamental consequences for how we live as people in society, for better or worse.

What’s the cutting edge in transportation systems right now? What are you guys talking about at the bar with your colleagues that no one else has heard about?

Evan Arnold: Self-driving cars are cutting edge now. Hopefully, unmanned planes and aerial vehicles, at least in the United States, will be coming soon. We’re not there yet, but other countries have already started, and it’s pretty impressive.

Do you think all cars will be self driving one day?

Arnold: I can envision a world where autonomous modes are mandatory for highways, at least. You know, you’re not allowed to take the wheel when you’re moving at high speeds. Theoretically, that will enable higher speeds. If we don’t have people behind the wheels, the cars could do the job better than we can.

Although the crash rates of autonomous vehicles are estimated to be about ten times that of human-driven cars, typically, the autonomous cars are being rear-ended and hit by people driving. One study found that about 60 percent of the collisions with AVs were rear-enders, and about 20 percent were side-swipes. If we got out of the way, that wouldn’t be so much of a problem.

I can envision a world where autonomous modes are mandatory for highways.

Terando: That brings up an interesting question. When we say “if we get out of the way,” that’s a decision to make, right?

Arnold: Oh, absolutely.

Terando: We subsume ourselves to a particular technology mode. What I usually think about is the human scale of people living, particularly, in cities. Several years ago there was a slide deck from an autonomous vehicle manufacturer, and their dream was to basically have gates along sidewalks so that humans wouldn’t get in the way of autonomous vehicles. I reacted very negatively to it. It was to sell a product. To do that they had to remove the parts that made it not work. That meant removing people, and cities are people.

Arnold: And that’s why I think there’ll be a differentiation between roads, city streets, and interstates. If we get to that point of having anything be fully autonomous, it’ll be thoroughfares. It’ll be transit. It won’t be your day to day. Because you’re exactly right.

Just recently, somewhere in California, an autonomous vehicle of some kind was not stopping. There were emergency services going on, and a fireman just had to go stand in front of it so it wouldn’t move. It was trying to cross a high pressure fireman’s hose. He was like, it can’t do that. It’ll pop. But there was no way to tell it to stop, so he just stood there until it was done.

Cities exist for humans, not machines

Monast: I think it brings up a good juxtaposition, or maybe just a question that we can think about in the future. It forces the issue between humans and machines. Our cities are currently built for machines, and the autonomous driver may force it to go even further towards machines because we want to clear the streetscape, make everything very predictable so the machines can understand their environment. To me, that’s not the optimal outcome for cities. Cities are built for humans. We’re going to have to explore how much of our city we want to dedicate towards machines. I think we’ve already gone way beyond what anybody would purposefully decide to do for machines in a city. We might be able to retract some of the progress towards machine environments that we’ve made the last 50, 75 years.

What do you mean when you say that our cities are built for machines?

Monast: Cars. Cars are machines, buses. But really, if you ever worked in a local planning department, we build our cities for fire trucks. The size of a fire truck determines the size of our turn radii on the streets, the size of a cul-de-sac. You may think this is way overbuilt, but it’s built for the fire truck. Speed bumps. All those things are all overruled by fire trucks. We also have parking lots for personal cars. With the advent of micromobility and smaller ways of moving around, I think we get to consider whether we want to re-envision the human scale in our cities.

With the advent of micromobility and smaller ways of moving around, I think we get to consider whether we want to re-envision the human scale in our cities.

Terando: Those are also choices, right? You go to other cities that were developed earlier than, say, the mid-20th century, and you don’t hear about them burning down all day long. London’s still there. Paris is still there. We even make choices about the appropriate size of a firetruck. A lot of these things are only optimal if you look at them from a particular point of view. Maybe fire trucks are optimized for one particular set of stakeholders, perhaps those who think that that’s the size of fire truck that you need. But that isn’t necessarily the case if you look at other objectives like, say, not having to have overbuilt road infrastructure. Our most valuable real estate in the city is the public space that we have, and we’ve ceded a lot of that to one particular machine, which is the automobile.

Arnold: Yeah, even in the old places you’re talking about: They’ve consumed as much as they can to make room for those vehicles. They’re not the old roads that you’re thinking of. These cities haven’t burned down, I imagine, because they’ve chewed up all the right of way they can to make it work for the larger vehicles.

Kai, you mentioned micromobility. What is micromobility, or microtransit?

Monast: Micromobility and microtransit are different concepts. Micromobility: They’re the electric scooters and the bike share programs. You see the little electric skateboards. It’s all those small devices that don’t take up much real estate to operate or to store.

There’s a large trend towards not only having personal micromobility devices, but having shared devices. With those, we can pull up an app and borrow a bike for a little while and then leave it wherever. That is one trend that’s really reducing what we call the “first mile/last mile” in an urban environment [the final distance you have to travel to your destination from your previous mode of transportation, like from your parking space or a bus or train stop].

With micromobility, in most cases, you have a network of sidewalks, bike lanes and ways that humans can safely move around outside the car travel lanes.

Microtransit is really for the other type of environment where it’s not safe to be a pedestrian or bicyclist, or maybe you don’t have the physical ability to be a pedestrian or bicyclist because you have a disability or mobility impairment. In those cases, your suburban areas, or your areas that just haven’t developed a good bicycle and pedestrian network, you can call a car with an app. It’s similar to your transportation network companies, but instead of it being run by a private company, it’s run by a public company. That way microtransit can provide public transportation options to people who don’t have cars so that they have about as much mobility as people with cars.

Almost like a shuttle sort of situation?

Monast: An on-demand shuttle. And it’s usually very low ridership in terms of who else is on the vehicle with you. You might have one or two other customers, but you’re operating in a sedan, so it’s very purpose-oriented towards the needs of those particular trips. It’s not like your fixed route bus, which carries a whole lot of people going to a lot of different places.

Terando: This is my opinion, but it’s also a little bit of a rebranding. We used to call it paratransit.

Monast: Or demand-response transport. We have had microtransit since 1983 in North Carolina, as demand-response in the rural areas. That’s when the North Carolina Public Transportation Association (NCPTA), a private, nonprofit organization, was incorporated and we started using federal funds for rural transportation in NC. In the urban areas, we’ve had it as paratransit since the 1960s, since the Civil Rights Act.

Then what is different about microtransit now?

Monast: A couple of things are different. The population that we were trying to serve was a very specific population of people with disabilities, elderly people. Now we’re trying to serve everyone with this technology. I use the word technology to refer to the mobility method. But it’s also what we call “tech-enabled,” which means that people can use their phones to order a trip. Through the technology of the phone, we know where the person is and where they want to go. It makes the process so much quicker and more seamless.

Previously, it was a phone call. You might need two days ahead of time to book that trip. If you didn’t have a car or you had a mobility impairment and you wanted to go out to lunch, you would have to plan that out two days ahead of time. Or if you “decided” that you were going to get sick and needed to go to a doctor’s appointment, you’d have to plan that out two days ahead of time.

With this tech-enabled microtransit, you can make on-demand, spontaneous trips. As we reduce the time between when you want the trip and when you receive the trip, it’s going to make that option closer to if someone had a personal car. If you have a personal car, you can just get in your car and go anytime you want. But if you don’t, or you can’t operate a car, you don’t have that freedom. That’s what microtransit is trying to accomplish.

The other thing that’s exciting about microtransit is that it’s politically attractive right now because it is able to serve different groups of people who may not have received very good service in the past. It’s being pushed at the federal level. Even at the state level, it’s very supported. As it gets implemented, the local support for this seems to be much higher than local support for regular, fixed route buses.

Do you think microtransit is immune to political division?

Monast: I do think it crosses the political boundaries because it is not just an urban solution; it bleeds into, or it really works even better in, the suburban, newly suburban-ising and the urban fringe communities. It also has an ability to increase access to work, education and healthcare in rural communities. I think that is very attractive, too. So it seems to meet the goals of all the political parties.

Terando: One thing I wanted to bring up again about micromobility is that it helps to address the fundamental trade-off that we typically deal with in human transportation, personal transportation. You’re always kind of fighting your own biology, in terms of physical exertion. If you have to get from point A to point B, and that’s a two mile walk, I might like to do that. It’s good for me. We always say we need to walk more. But if it’s hot out, or if it’s raining, or you’re in a hurry, etc, your likelihood of doing that really drops.

Micromobility really gives you another option on those short trips. And because many bikes or scooters are electrified, you’re getting over that mental barrier of the physical exertion it will take to get there. If you use the bike share, which, here, are either electric or electric assist, you can get there really fast. In some busy areas, like around Hillsborough Street, you’ll get there faster than driving, when you account for parking and getting from your car to where you’re going.

It’s a really important innovation. In one sense, we’ve had electrified vehicles since cars were invented. But now with phone apps and battery technology we’re able to call those on demand services and share them. This transportation is becoming so reliable and available that people may feel more comfortable not relying on private automobiles as their primary mode of transportation, which have all these other externalities that we know about when it comes to society, the environment, climate change, etc, etc.

This transportation is becoming so reliable and available that people may feel more comfortable not relying on private automobiles as their primary mode of transportation.

Is there ever a world where no one has a private car?

Terando: Talk about the long view. Did you all see that New York Times Op-Ed that came out about two weeks ago? It was a long view on human population, where really, no matter the demographic model, we expect human population to crash over the next 200 to 500 years purely because of demographic trends. As humans enter into advanced levels of society, the birth rates drop, so unless the tech billionaires are going to get their wish and we’re going to have immortality (which I’m guessing would only be for them, anyway) there’s pretty high confidence that human population levels will drop back to where they were before the Industrial Revolution over the next 500 years or so.

That’s a world where you could see all sorts of big changes in our economy. Will there be any car companies left because you just don’t have the inexorable increase in demand driving more production like we’ve had? Or are we going to really mess up the climate before then and we’ll have that going on as well?

We haven’t really thought through those questions yet. There are all these singularity points that are kind of coming to a head in the next – I mean, beyond our lifetimes, but we’re sort of the first generation that’s really been able to see these things and contemplate them. We’re just now starting to think about those consequences.

Now I’m scared.

Terando: Check it out. Check out that op-ed.

Monast: I’m thinking specifically about the personal vehicle. I’m going to change the word in your question from “car” to vehicle. I could see that—everyone probably will still have access to what looks like a personal vehicle. Now whether it’s yours, and you can put bumper stickers on it, and it’s dedicated to you, I don’t know if that’s necessary in the future. I almost think of it as a subscription service, or maybe a condo-esque situation, where you might own the inside and you rent or pay a subscription for the outside and the motor and all that stuff for the vehicle.

Everyone probably will still have access to what looks like a personal vehicle. Now whether it’s yours, and you can put bumper stickers on it, and it’s dedicated to you, I don’t know if that’s necessary in the future. I almost think of it as a subscription service.

I do think there is an inefficiency in a lot of our use of the transportation system. My car is sitting idle right now. It’s not being used, and it’s taking up space, and that does seem inefficient. As it gets easier to share, I think we’ll see a trend towards way more sharing going on with vehicles.

Zipcar – the shared car you can find on your phone – launched in Cambridge in 2000. It took maybe a decade for it to catch on in places like Raleigh, or even New York. Other car share services have popped up since then. Still, reports suggest people aren’t great at sharing and think these services are expensive, so they’re not used as often as they could be. Why might that be?

Terando: We don’t have the system set up yet. In most places not owning a car still seems to not make economic sense to people. I live downtown, and I get around mainly by biking, walking, and the bus. But even I own a car, and it sits idle, maybe 95% of the time.

We don’t quite have the long and short term incentives set up to make those trips make sense. For instance, if I go to the mountains, or go to the beach: In North Carolina, you can’t take a train to either of those places right now. That would be very convenient. Whereas in Europe, or even New York, you could. We have a lot of work to do to make those economics work out. Maybe those economics will be forced. If you look at the new MSRP, the Manufacturer’s Suggested Retail Prices, on cars, and particularly EVs, they are astronomical. That might force the issue to a tipping point. Somewhere there’s an inflection point where the economics will make sense. Right now in the US, it just doesn’t.

Arnold: I think all that’s true for an urban environment. But in suburban and rural areas, we’re much further away. Truly the jobs in the rural communities wouldn’t support that. People living in rural areas work far from where they live. They might work in agriculture or another area that demands a vehicle. So while having mobility options and not needing a car is true here (you’re a great example of it), I live two miles away, and the rideshare, bikes and scooters cut off between here and my house. So it’s truly not an option. That boundary is a political one, and for good reasons. The types of roads in those suburban and rural spaces don’t have the capacity to share the road with pedestrians so much or so easily. We’re still quite a ways away from even the fringe, even the suburban, supporting that lifestyle.

Monast: But what I think we’re saying is, there aren’t enough mobility choices for us, in most of this country, to think that a car is not mandatory. And when we create convenient, affordable mobility options, then the car becomes a choice instead of a requirement.

When we create convenient, affordable mobility options, then the car becomes a choice instead of a requirement.

Terando: And we’ve amplified that system. We have created positive feedbacks that reinforce that. To your point, it’s not just highways and cities where everything’s a two lane street. We have big roads like Capital Boulevard, Western Boulevard, South Saunders. We have big roads in town too. Through our engineering and design systems we have kind of signaled that this is how you should be getting around. Where we build housing has reinforced that as well. It’s slowly changing, but for many decades, we banned almost any other type of building use within residential areas.

Banned?

Terando: Like shops. Through zoning. We had single use zoning: Residential areas are only for residential. You could not build a corner store. You still can’t technically, really in Raleigh, unless it’s grandfathered in. So for people to be able to not drive places, we almost literally made it illegal. It was like we said: you cannot put any sort of services that are within a normal human scale in our cities. And we did that for many decades. Unwinding that system takes a lot of time.

Speaking of city zoning, say you get an opportunity to build a transportation system for a city in the future. There’s no political or cultural boundaries in your way. What does it look like?

Monast: Start with the human. Start with the children. If it’s a good place for a child to move around, it’s a good place for anybody. Let’s think about that human space. Let’s orient the buildings and place them around sidewalks and shared-use paths. Then we can go and figure out: Where do we move the goods? How do we move the goods? And how do we move people faster along line hauls, fixed routes, subway, metro systems, things like that? But let’s start with the human scale.

Start with the children. If it’s a good place for a child to move around, it’s a good place for anybody.

Terando: I would totally agree with that, and I think that’s where you start to see why that’s a challenge, too. There are other actors involved, and they have incentives to not think in that way. For example, car companies want to sell cars.

Are they contributing to city politics?

Terando: I think implicitly.

Arnold: Yeah. Not at a micro level. But the city design, from the ground up, is based on cars today.

Monast: It’s not just the car companies. Consider a fast food restaurant that has a drive-thru window and a parking lot. If you walk to that, you should get a discount. You should pay less because you didn’t have to support all that pavement and all that land. But we build it into the price, and we basically don’t incentivize the right thing. We either treat everything equally, or often, we disincentivize the right thing. For instance, if you pay a bus fare, you know exactly how much it costs for you to take that trip. But if you get in your car, it’s a very lumpy cost with cars. You buy the vehicle, maybe once every 10 years. You pay insurance, maybe once a month, maybe once a year. You purchase gas, maybe every week or two. You don’t really know how much that one trip costs you. But when you get on the bus, you do. And that fare is an impediment. The fact that you have to do that calculation in your head is an impediment to riding the bus. So people who have a car, who don’t know how much that trip in their car cost, will just take the car rather than pay the bus fare.

What if we go beyond roads and cars? I want to know what kind of vehicles are even out there in the future. Is there a Jetsons-style flying car? Some kind of autonomous flying vehicle? Do we have underground highways? Right now, in the UK, a company is building helium blimps to take people on short trips. What other things can you imagine?

Terando: All right. I’ll give you my long view, perfect transportation system. It is extremely boring.

Ugh.

Terando: Yeah. It is. Because a lot of this stuff is not crazy high-end technology. It’s an electrified system. We’ve moved to electricity away from internal combustion engines. And things are closer together because we get back to more of a human scale. We’ve built vehicles that can take us very far, very fast, but there’s all these other consequences to them. So I’m starting from the human scale, the kids scale, and I’m asking: What advances the human condition? What advances our ability to lead full lives and not have to take on the added, extra risk of the system we’ve designed now and the added, extra cost to the planet?

It’s a very boring vision in some ways because it’s not flying cars. It’s not underground highways. It’s just getting back to a human scale of a city. But throw in some electrification. Throw in some better infrastructure to help you get out of the rain if you’re on a bike or something like that. And then off you go.

It’s a very boring vision in some ways because it’s not flying cars … It’s just getting back to a human scale of a city. But throw in some electrification. Throw in some better infrastructure to help you get out of the rain if you’re on a bike … And then off you go.

Is it too late for high speed rail in the U.S.? What would it take to make it happen?

Terando: Technically no it’s not too late. It’s just a matter of policy choices. Some areas might be suitable to run high speed rail (HSR) along or in-between railroad tracks. We will probably be seeing new HSR lines coming into service in the next several years. The Brightline rail line in Florida is a privately operated line that runs at 125mph. The new Acela lines on the Northeast Corridor will be traveling at 160mph in sections, and eventually could travel at speeds of 186 mph.

I mean, humans had thousands of years in cities where they sort of organically developed ways to move around at a human scale because they had no other option. We’ve kind of torn that apart and thrown it all around. Instead of trying to literally reinvent the wheel, we kind of need to just go back to how humans have organically done these things in the past. In a way, you can think of humans as these self-organizing systems that have already figured out a lot of this stuff because that’s what optimized on its own for humans to be able to live together in cities.

Instead of trying to literally reinvent the wheel, we kind of need to just go back to how humans have organically done these things in the past.

Monast: I agree. I walked here from the other part of campus. And every time I walk here, I go through a tunnel underneath train tracks, and I estimate that during a typical day, probably 20,000 person trips go through that tunnel and maybe 500 person trips use the train tracks. And it strikes me as: How is this fair that I have to give up the surface of this planet and go underneath it for this railroad line? Why is the railroad line not going underneath me or above me? From a human point of view, I feel like that’s an unfair treatment. I want the surface of the planet, for my own personal mobility.

Arnold: That’s how I feel about Western Boulevard.

Monast: It’s the same thing, right? I predict that we’re going to get the surface of the planet back for human scale mobility, and we will raise or lower or push to the outside the barriers, the I-40s, the train tracks. And then Evan is going to come into play with what happens off the surface.

Arnold: Yeah, sure. The third dimension is going to give us a lot in terms of capacity.

Wait, third dimension?

Arnold: Being air. Leaving the ground. Leaving that precious surface of the earth that Kai wants back so badly.

Traffic in the sky

You know, it’s going to be a varied approach. In an urban setting, it might just never work. It works in New York City because they’ve got rivers to land on and tall buildings. But in a medium-sized city like Raleigh, most people aren’t going to land on the rooftops of buildings, and there’s not many other places to set an aircraft down. We could design for it. We could build what’s called “vertiports” if that becomes a demand. But then the question becomes: How far are you going from that center, from that vertiport? Is it a short-term-only model, where you’re just going to the surrounding communities? Or are you really going to try and leave from a city center and go to Charlotte, go to Washington DC, leave the state, go all the way to the beach or the mountains? Those trips will be defined by vehicle design, and we’re not really sure where it’s going to fall. It could change greatly over the next several years.

Okay, right. You can do anything with that extra space above us. You mention aircrafts for different kinds of trips depending on design. Are people right now working on building little flying things that can take people around? What is this air transportation?

Arnold: In the world of aviation, we call this topic “advanced air mobility.” It’s a broadening of the term urban air mobility, which was the original coin of air taxis flying around cities, but specifically, getting away from the helicopter model of a pilot on board, relatively expensive, and fossil fuel burning. These systems are largely electrified, battery-driven.

The big problem comes back to: How do we access that? In our airports we’re able to get many people off the ground all at once, and we do this consistently throughout the day. If you have one small vertiport, like I just sort of hypothesized, and we’re doing one-in, one-out flights, it’s going to take a lot of time. The plane is going to land. People are going to get off. And when I say people, I mean two, four, maybe eight are going to get off. Two, four, eight people are going to get back on, and it’s going to leave. It’s not going to be hundreds of flights if you’re geographically bound.

Now, if they’re stationed out in an airport, they can do lots of operations. And then—this is a regulatory or a policy question—if all of that air travel still demands a TSA-level screening, then it’s not going to be efficient for a short trip. If I have to go to the vertiport, wait in line, wait for my aircraft to be ready, get on, go to the next place, get off and then go the last mile to whatever my destination is, on a short trip, there’s no way that will outpace even car mobility, or the micromobility options.

And so these are just things that have to be small because there’s nowhere to put them? And maybe technically they can only handle so many people?

Arnold: Yeah. Capacity is a question. Charging is a question. If an aircraft comes in and needs to charge, are we going to have the space to maintain all that? That’s why our airports are massive. Our airports are huge. They take up a lot of real estate, both for the human interaction of loading and unloading, as well as all the maintenance facilities and in this case, the aviation fuel infrastructure. So just saying, oh, well, all we need is the space for a heliport is really not true. We need a lot more to support consistent operations than just a forty-by-forty square.

I feel like you’re saying it’s impossible to use this third space, but you were excited about it. So how does this work?

Arnold: I’m excited about it more on a regional level. Again, we’re talking about: What market will it serve? In those very urban environments, I think it’s going to be more difficult. But then at a larger vehicle size, but still smaller than traditional aviation and potentially still segmented from traditional, major airports—they’re going to continue doing their type of operations: international, long haul flights, cargo flights—there could be a regional air mobility demand of the interstate, or slightly-out-of-state flights that bring value, either commercially or recreationally, and get people off the roads.

They have this in Europe, right? You can take the cheap, little planes. They’re just not electric…

Arnold: But you’re still using your typical airport infrastructure.

Okay.

Arnold: So you’re on the plane with 100 people. You go to the normal airport. We still have those flights in the United States. I just flew from Charlotte to Dayton, Ohio, on a very old style aircraft. That’s what you’re referring to, the Ryanairs of the world?

Yeah.

Arnold: This is more like they’re flying in, I think Japan, China and the UAE. It’s two to eight passengers. There’s no pilot on board. You load up with your cargo. You’ve got a destination in mind, and it flies for itself. There is a segment there, but the eventual market that it serves is to be seen.

I see. Do you foresee lots more of these aircrafts in the air? And also, with companies like Amazon using drones more, we’re probably going to have a lot more drones in the air.

Arnold: Absolutely.

So then what do we do?

Arnold: We have to manage our traffic. We call that UTM, or unmanned traffic management. There are a lot of opinions in the room on that right now because we’re still exploring that space. Will it be “highways in the sky”—navigable lanes that they have to stay within during transit? Or will it be an air traffic control-based system? That’s going to be a huge amount of demand on the air traffic controllers and that system, so that’s unlikely. Will it be file and fly? It doesn’t have to be a specific highway in the sky, one solid route. If I tell you I’m going from A to B in this direction, and I file that flight plan for a certain time period, then that airspace is locked up until my flight is done and no one else can file a path that crosses it.

All of those things said, then if we start using this for emergency systems, we’ll have to find a way to take precedence over whatever is scheduled. There are lots of use cases that involve drones for emergency response, both on-demand, 911-called style and then also major disaster response, for wildfires, hurricanes, flooding, things like that.

Right, because drones could do the work too. You could have a robot fix people, remote surgery. I don’t know if I’m on the same page.

Arnold: I’m sure that is being researched by someone else. Right now we’re just trying to get the people what they need. You call 911 because someone dropped in front of you. They may need CPR and a defibrillator. In a time sensitive emergency response, we can get there faster than an ambulance. Similar stories for the overdose medication Narcan, for anaphylactic shock, epi pens, most allergic reactions. Some antivenoms are relatively safe for a bystander to administer. These are cases that don’t need an EMT or other medical professional there, and if we can beat the ambulance, then survivability increases greatly.

That’s cool.

Arnold: Yeah. The other applications are things like search and rescue. For wildfires, we can drop fire suppression. We can also drop fire activation [prescribed burns] to try and burn the cuts in front of an oncoming wildfire. Normally we drop people in, and they burn a path.

Terando: In the Southeast prescribed fire is huge. We do more prescribed fire here than any other place in the US. Drones can start to play a huge role in that in terms of safely starting fires and monitoring them.

Arnold: But all that to say, yes, we will have a vastly larger number of aircraft in the sky. They will be flying lower than what we’re typically used to in a greater quantity. And they will have to be managed by something.

We will have a vastly larger number of aircraft in the sky. They will be flying lower than what we’re typically used to in a greater quantity. And they will have to be managed by something.

Terando: I think the trick is going to be fundamentally on the physics. It takes more energy to move through the air. You don’t get the benefit of momentum like you do on the ground. You’re talking about Ryanair: Europe is starting to ban short haul domestic flights because of the climate impact. Instead, they’ve put so much investment into high speed rail. Now instead of six to eight people, you’re talking one thousand people, and you’re going three hundred miles an hour. So you take advantage of that momentum, just the basic physics again. The trade-off you’re describing about emergency situations makes sense because the time benefit you might get from moving in the air outweighs the energy cost you get from having to get into and move through the air. You accept the trade-off because that cost-benefit works out. As far as a major transportation mode, I think it’s going to be hard to make it cost effective, to make it work for more than just high income individuals.

Arnold: You’re absolutely correct. There are places that are exploring that and even, I don’t want to say fighting against it, but certainly being mindful of it. Los Angeles is one of our worst traffic offenders. It’s a gridlocked city nearly 24 hours a day. They’re obviously seeking the air as an alternative. Very quickly people realized, well, if this is going to be a solution only for the wealthy, then it’s A) not going to drastically change our transportation environment because everyone else is still going to be on the ground. And B) not something worth investing municipal dollars in if it’s not serving the greater community. It’s being explored. I don’t know that the urban-focused air mobility will ever really take precedence over the micromobility and other things due to the time that it’s going to require and the cost associated, but I think there’s a market out there for it.

Terando: Wait for transporter technology. Star Trek.

Yeah. Well, is that possible? Will we teleport?

Monast: Sounds fun, but I don’t see it happening.

Terando: I mean, for multicellular organisms, it’s a very tall order. There are some interesting things going on in quantum physics, having stuff flash around, little electrons and things like that, but on the macro scale, I don’t know. If you’re talking about the long view, let’s do this again in a million years and see what humans have done. If we’re still around by then, maybe at that point. We’re talking about a really long view for something like that.

Arnold: I’ll take falling asleep in the back of a self driving car for now. You get in. You tell it where you want to go. You wake up, and you’re there. That’s teleporting to me.

I’ll take falling asleep in the back of a self driving car for now. You get in. You tell it where you want to go. You wake up, and you’re there. That’s teleporting to me.

Terando: That’s true. Honestly, you know what? I do that on the bus sometimes. We’ve already got it on the bus.

The pandemic really changed transportation. People are at home. We’re on Zoom. We’re wanting more goods. Is there a world where we’re not moving around?

Terando: You mean, like WALL-E?

That’s exactly what I picture.

Arnold: Back to your question about if we had a blank slate to build a city—why do we need a city? Why do we need a concentrated human environment? I like space. I don’t ever want to live in an apartment in the city. But if I’m on Zoom for work, and I can order my packages remotely, I still might not need a car, but I don’t want to live in a city.

I counter your view. I work at home. I live near downtown, and I still feel like there’s not enough city. There’s not enough people around. I get tired of being inside all day. I guess it’s personal preference.

Arnold: There’s a lot of things you can do with space and time. Right? If you’re looking for opportunity, then there’s a whole world out there.

Terando: You’re bringing up a good point. This is what I meant about different actors and preferences. It’s hard to predict things completely going away or completely shifting because there’s always going to be push and pull and people with different values and objectives. Again, prior to the Industrial Revolution, we had thousands of years of humans living in cities. I think there’s just quite the track record now that cities are the means by which economic activity and social activity amplify each other. It’s by way of the proximity of people. There’s just so much evidence of that that I don’t see cities going away. I think it’s just a matter of—for transportation, when you’re talking about that—can we maximize the amount of trips people do purely out of enjoyment or satisfaction or because they really want to do that? Like you want to walk to the park. You want to walk to the bar. You want to walk to school. Can we design cities and build cities that help maximize the proportion of the trips that are all for things that we are choosing to do because we want to not because we are stuck and have to.

Can we design cities and build cities that help maximize the proportion of the trips that are all for things that we are choosing to do because we want to not because we are stuck and have to.

Like the pandemic, climate change will transform transportation as we know it. Seas and temperatures will rise. Ice caps will melt. Stronger storms will hit more often. How do you see transportation changing with the climate and how can we adapt? It may help to picture your dream – or your nightmare.

Terando: Well, there’s our highly regulated systems which are going to have to be re-regulated. Like air traffic. We’re already seeing issues with just the tires we use. The tarmacs are getting too hot, and it’s causing delays for takeoffs and landings. Those are probably solvable problems. We will develop some better rubber or whatever. Hopefully it won’t require us to make orangutans go extinct in Indonesia, or something like that. But it might.

Those are some of the immediate things we’re going to have to think about. Extreme heat: I’m talking temperatures getting to over 100, over 120, over 140 degrees Fahrenheit in places not used to that type of heat. Many places were not designed to handle those kinds of temperatures. I think we haven’t probably reconciled enough yet with the potential consequences of that kind of extreme heat. Then on the opposite end, the Arctic melting. That’s going to destroy a lot of roads because of permafrost melt. We have whole systems built on the ground being frozen. You’re basically just putting a concrete slab down on permafrost. And then constant flooding. We’ve been dealing with that in North Carolina along the coast, along Highway 12, ever since I’ve been in North Carolina, 20 years. That problem is not going away.

You talk about a long view, that’s a 10,000 year thing we are now going to have to deal with because the long tail of sea level rise, that momentum it takes to actually melt ice caps, once you start that process, to reach a new equilibrium between the amount of ice we had in Greenland and Antarctica compared to the average temperature of the Earth, that’s a very long process. We will have sea level rise. The seas will continue to rise now for thousands of years. That is something we are going to have to figure out how to deal with.

About the interviewees

Adam Terando is a Research Ecologist with the US Geological Survey at the Southeast Climate Science Center, and an Adjunct Professor with the Applied Ecology Department at North Carolina State University. His current research focuses on the impacts of climate and land use change on ecosystems and the complex human-environment relationships that drive these processes.

Evan Arnold is a Research Associate with the Institute for Transportation Research and Education in Raleigh, NC. He holds a B.S. in Aerospace Engineering from North Carolina State University. He has been a Research Associate for ITRE’s UAS program since its inception in 2015.

Kai Monast is the Director of the Public Transportation Group at the Institute for Transportation Research and Education at NC State University. Kai works closely with public transportation systems, State Departments of Transportation, and other industry stakeholders to conduct research, provide training, assist with technology implementations, and advise on operations and improvements in efficiency.