Campus Tunnel Marks 50 Years of Free Speech

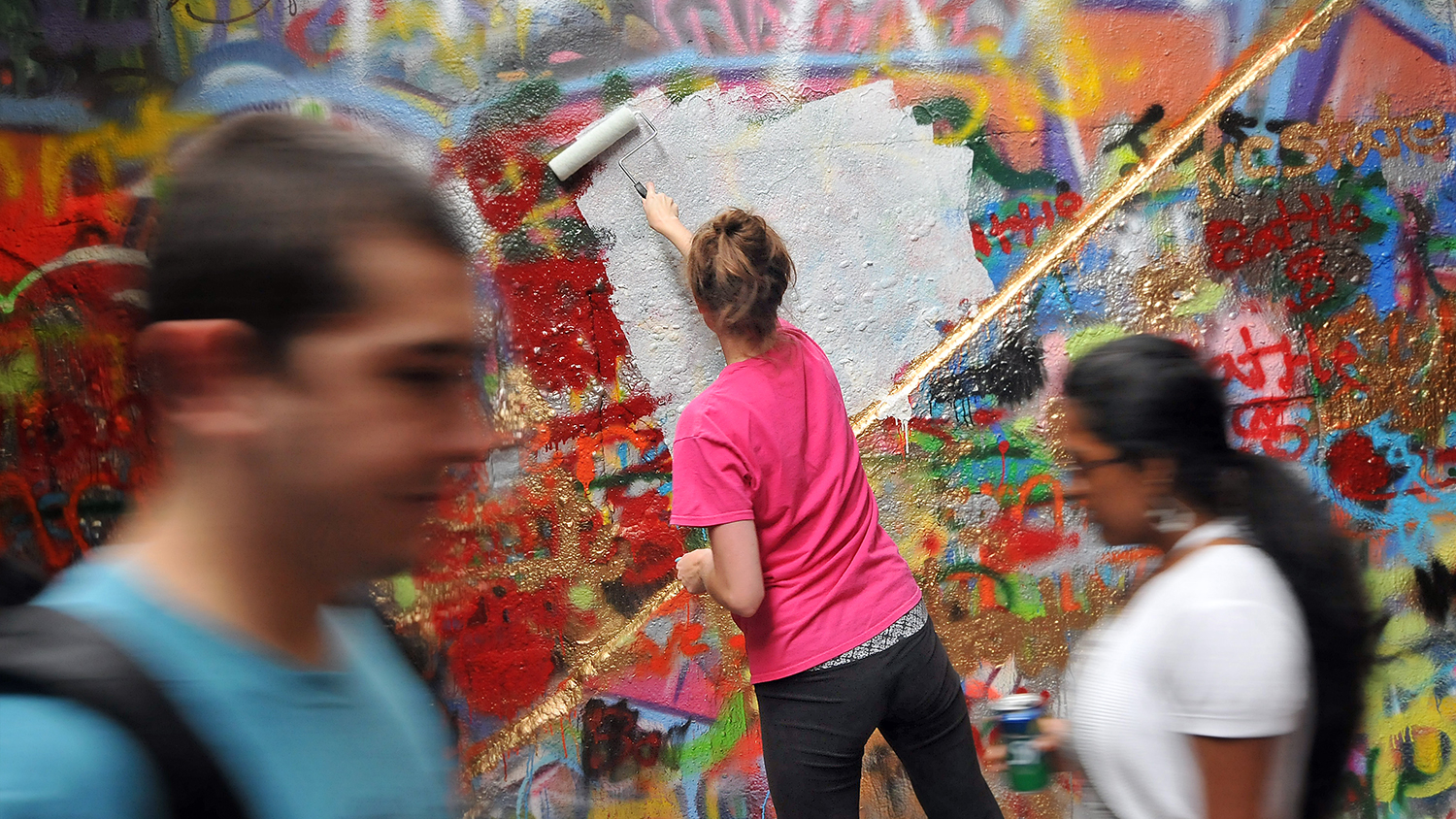

On a cold November evening 50 years ago last month, a dozen or so members of NC State’s student government spent $20 from its general fund to host the inaugural “paint-in” at what used to be called the Student Supply Store tunnel, the longest, widest and most heavily used pedestrian tunnel on campus.

That evening—Nov. 9, 1967—was the official birth of the university’s now-iconic Free Expression Tunnel, the oft-painted, sometimes-hated underpass that is a unique tribute to the First Amendment on an American college campus.

“It’s a place on campus where anybody can write anything, a place where we can uphold and respect the intentions of the First Amendment,” says Mike Mullen, vice chancellor and dean of academic and student affairs. “It’s a wonderful tradition. It’s something everybody sees almost every day. It might be easier on us all if we just painted over it, but it’s a place where students can learn to freely express themselves.”

“It’s a place on campus where anybody can write anything, a place where we can uphold and respect the intentions of the First Amendment,” says Mike Mullen, vice chancellor and dean of academic and student affairs. “It’s a wonderful tradition. It’s something everybody sees almost every day. It might be easier on us all if we just painted over it, but it’s a place where students can learn to freely express themselves.”

The Free Expression Tunnel is one of nine university-chosen Hallowed Places, a group of irreplaceable, iconic buildings or locations on campus that have accrued special meaning. It’s likely being repainted as you read this, with new coats being applied on top of day-old art, organizational announcements and self-expression. Midway through the tunnel, there’s an inches-deep indention that shows the thickness of five decades’ worth of paint.

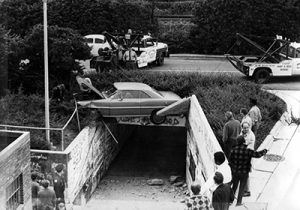

Certainly, few places mean more to students and alumni than the tunnel that was originally built in 1939 as a Works Progress Administration project to connect two sides of campus for pedestrian use. Two other tunnels were eventually built for pedestrian access, and all were frequent targets for graffiti.

The 50-year anniversary commemorates an agreement between students and university administration that the largest tunnel would become a permanent place where students could visually express themselves in any way they see fit, while the other tunnels would remain free of graffiti.

It’s a self-monitored canvas that changes every single day.

The tunnel caused Vice Chancellor Emeritus of Student Affairs Thomas Stafford more headaches than anything else in his four decades of service to the university — yet he remains one of its strongest proponents.

“It is unique and important,” Stafford says. “It is an ever-changing monument to the First Amendment, and a great educational opportunity for our students. It teaches them the importance of those freedoms, and it teaches them that those freedoms come with great responsibility.

“It’s a place that people want to see when they come to campus. People want to know about it. Students walk through it every day, so it is the perfect place to tell someone happy birthday, to promote an event or make a political or social comment.”

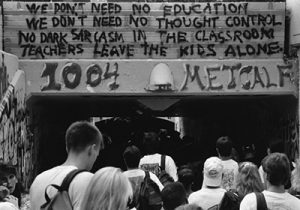

The first complaint about the space was published before the initial paint was even dry, when student Reinhard Koch called the painted tunnel “a scarred corpse of a great idea” in Technician’s first printed edition after the paint-in.

“I’m saddened to see what has happened to the SSS tunnel,” Koch wrote. “What at first was a showplace of some real artistry and imagination by State students has been prostituted into a billboard for bigots and morons. … The tunnel will soon be a splotchy mess.”

“I’m saddened to see what has happened to the SSS tunnel,” Koch wrote. “What at first was a showplace of some real artistry and imagination by State students has been prostituted into a billboard for bigots and morons. … The tunnel will soon be a splotchy mess.”

According to Technician, some of the first statements painted in the tunnel were:

- “Mary Jane and I are having a good time and there’s nothing you can do about it, Mark.”

- “Jesus saves … Green Stamps.”

- “P.P. owes Porter, Hilton, Crawley, Hanna and Lewis $207.79.”

The latter referred to the amount of money five students were charged to repaint the tunnel leading to Reynolds Coliseum with red-and-white stripes earlier that year. They claimed in a letter to the Technician editor that they were promised a refund if painting one of the tunnels ever became a tradition.

That tradition has certainly taken root, even when cringeworthy statements appear (no matter how briefly) before self-policing fellow students paint over them.

“Sometimes our students who have seen hurtful messages would like us to post guidelines about what can and cannot be posted, but that would make it a civil discourse tunnel, not a free expression tunnel,” Mullen says. “We tell them the best way to fight free speech is with free speech.”

For J Hallen, a senior from Cary who serves as Student Government’s director of diversity outreach, the tunnel has caused some unpleasantness in her four years on campus, though negative occurrences seem to have declined in recent years, in her opinion. Walking through the tunnel almost every day has strengthened her sense of campus community.

“It certainly has enhanced my college experience,” Hallen says. “The good messages that you see in the tunnel are an affirmation of how far we have come with issues of diversity and inclusion. The negative messages show you that there is still work to be done, that there are still reasons to keep your guard up.

“But it is a good and open forum for everyone on campus.”

The tunnel can be seen as a useful counterpoint to social media in the way it breaks passersby out of their respective echo chambers.

“Sometimes, in social media, we live in a bubble of only seeing the messages of those people we are connected with,” Hallen says. “The Free Expression Tunnel is a more open forum that is seen every day by a larger and more diverse audience: students, faculty, staff, visitors.”

For Olivia Shipp, a senior in nutrition science from Charlotte who serves as vice president of the Alumni Association Student Ambassadors, the tunnel is an indispensable place on campus that she knew about long before she enrolled and has cherished during her time here.

“When I was touring NC State four years ago, it was one of the places I knew about and wanted to see when I was here,” Shipp says. “I think it’s a great way to advertise things that are happening on campus. Every year before the State-UNC basketball game, we have the Ram Roast, where we protect each end of the tunnel from UNC students who used to come over and paint the tunnel blue.”

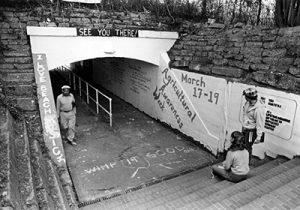

In January 1978, after graffiti began to creep outside the tunnel’s entryways and into the other two tunnels, more specific rules were established to keep all painting inside the interior of what was rebranded as the Free Expression Tunnel.

During 2005-2006, the tunnel was closed while new entries with accessible ramps and new boundaries were built, turning the rock-pile entrances into brick-lined gateways.

On many occasions, the tunnel has featured highly artistic stylized graffiti worthy of Associate Professor of Communication Ed Funkhouser’s daily snapshot of the tunnel’s content. It also functioned as a brick-and-mortar precursor to social media, a place where students could send messages to classmates, announce events and share ideas. In recent years, it has been the site of Monday night gatherings where local artists and students come together to freestyle, sing, play instruments, recite poetry and network.

The tunnel has also caused considerable embarrassment or consternation to campus administrators when obscene or inappropriate graffiti appeared. Ultimately, however, the Free Expression Tunnel provides an opportunity for students to learn the importance of truly free expression.

Even when the tunnel is darkened by controversy or poor taste, there’s always someone else with a paintbrush willing to offer an alternative viewpoint.

And a bright light on either end.

This post was originally published in NC State News.

- Categories: