GOHA Affiliate Member Yogesh Saini Advances Understanding of Cystic Fibrosis

A team of NC State veterinary scientists led by Dr. Yogesh Saini thought that a chemotherapy drug that blocks a receptor called EGFR would reduce lung inflammation and thick mucus in a cystic fibrosis model. Surprisingly, it does the opposite.

By Bethany Brookshire

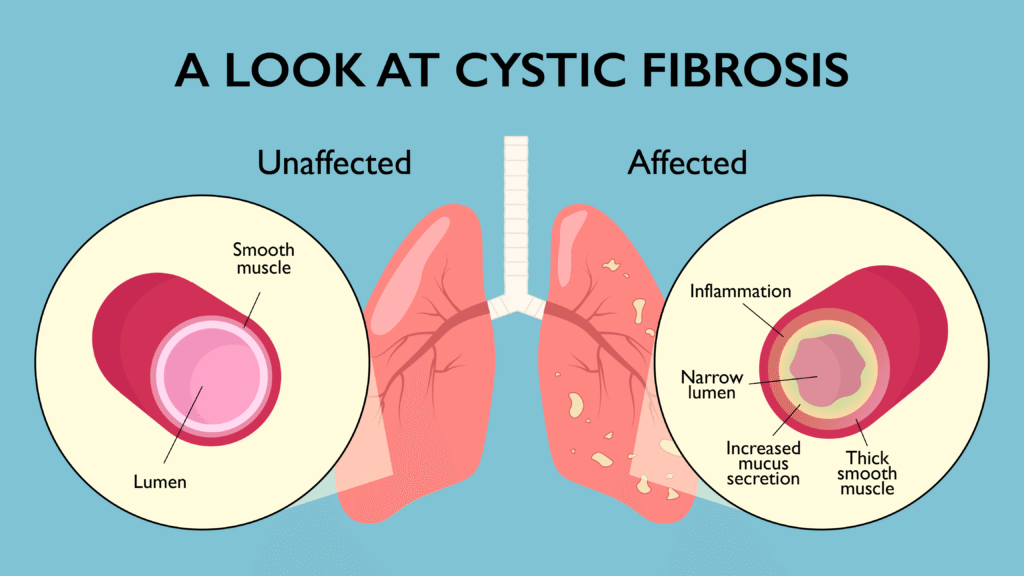

People with cystic fibrosis are in a constant battle with the thick, sticky mucus that builds up in the airways of their lungs. But while the genetic disease is due to mutations in one specific gene, it takes a score of proteins to make mucus, and not all of them are fully understood.

In a new study, research scholar Ishita Choudhary and Dr. Yogesh Saini, pulmonary immunologists at the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine, and colleagues investigated the role of an epidermal growth factor receptor, a protein on the surface of airway epithelial cells, in contributing to the thick mucus in cystic fibrosis. They found that CF-model mice lacking the receptor have increased lung inflammation, more bacterial loads and more mucus buildup compared with those with a normal functional receptor, suggesting that drugs inhibiting this receptor may be the ones that CF patients need to avoid.

Cystic fibrosis is caused by mutations to a gene called the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator that cause cells in CF patients to absorb more salt. That salt pulls more water into cells lining the airway, digestive tract and more. While those cells end up stuffed with salt and water, they leave the liquid layer on top of them much drier than it should be.

That liquid layer is full of mucins — big, heavy proteins that soak up water and become gels. Without enough water to soak the proteins, the mucus along the airways of CF patients becomes thick, like a hard Jello.

“The solids are also getting concentrated,” Choudhary explains. “So this mucus is kind of like building up into a static plug.”

CF patients struggle with this extra mucus, which forms a fertile ground for rampant colonization of harmful bacteria species.

“There are two signaling pathways that have been known to contribute to mucus obstruction,” Choudhary says. One is well known, but the other, through a receptor for epidermal growth factor, or EGFR, is not.

To understand the role EGFR might play in CF, researchers in the Saini group and their colleagues bred four groups of mice and examined their airways. Two groups of mice were normal, and two were a model for CF called Tg+. Then, in one group of normal mice and one group of Tg+ mice, the scientists knocked out the gene for EGFR in in the cells lining the airways of their lungs.

In the normal mice, the absence of EGFR didn’t seem to matter much. The animals had no differences in inflammation or mucus production.

Tg+ mice, though, already tend to have high expression of genes associated with inflammation. Immune cells and mucus accumulate further in their airways. In short, take away the EGFR gene, and their symptoms get worse.

“Think of a cop doing surveillance in the streets,” Saini says. In CF patients (and Tg+ mice), immune wand epithelial cells or cops are on high alert all the time. “They are waiting for any apparent material or any threat that we have inhaled.”

How Mucus Escalators Function

In the study, Tg+ mice showed more signs of inflammation, their airways became clogged with immune cell cops and even more mucus plugged their airways. “When we have a cold and runny nose, we spit out mucus,” Saini says. “This is what it is.”

Because of their thick, dry mucus, Tg+ mice and CF patients alike have trouble getting rid of the bacteria that they breathe in. Normally, our mucus acts as an escalator, patiently moving bacteria up in our airways, for us to eventually cough them up and swallow them so our tough digestive systems can destroy them for good.

“When it is dehydrated, the mucociliary escalator cannot function properly,” Choudhary explains.

In normal mice, their mucus escalators worked fine — even without EGFR. But Tg+ mice had slower escalators, with about 50 percent of them having bacteria sitting in their airways. And without EGFR, the Tg+’s escalators were severely overwhelmed — 92 percent of them had bacteria.

The results have a potentially important message: Some drugs inhibit EGFR. These drugs are usually used to stop cell growth in the treatment of some cancers, such as lung, breast and pancreatic cancer. The drugs are also being tested on asthma.

“Giving an EGFR inhibitor to CF patients is not a common thing,” Choudhary says. But if someone has a disease like CF, where the lungs are already inflamed and full of mucus, “one needs to be really cautious.”

Choudhary, Saini and their colleagues hope to continue their work using EGFR-inhibiting drugs. This current study looked only at specific cells of the lungs. “If we use the pharmacological inhibitors in the mice that will target all the cells, we may see contradictory responses,” Saini says.

The results were a shock for Choudhary and Saini. “We were really hoping that this will benefit these mice, because this mucus production pathway is specific and pathogenic,” Saini says. “We were surprised to see that it was going the other way.”

It’s a good reminder, he says, that scientists should always approach their work with an open mind. “As a scientist, we always have to look at both possibilities.”

Bethany Brookshire is a freelance science journalist and author of the book “Pests: How Humans Create Animal Villains.” Her work has appeared in Science News, Science News Explores, The Washington Post, The New York Times, Slate, The Guardian, The Atlantic and other outlets.

This post was originally published in Veterinary Medicine News.

- Categories: